Museum - The new homelands

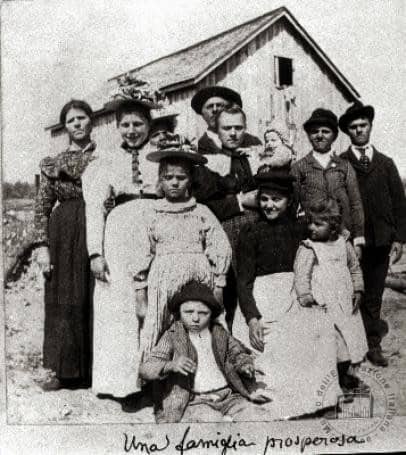

City founders and colonizers

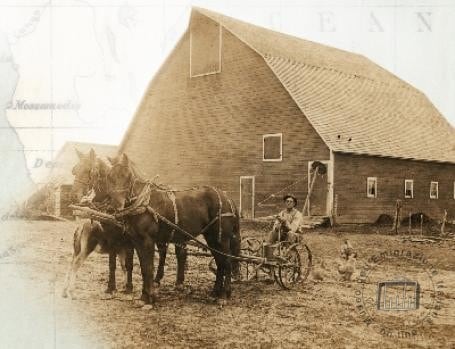

Italian immigration to the United States, although largely composed of farmers, stayed away from agriculture with exceptions in the southern states. Tontitown, Arkansas, a colony founded in 1898 and still with a strong Italian component, and, in California, the Italian-Swiss Agricoltural Colony, established in 1881 in Sonoma Valley at the behest of Andrea Sbarboro, a pioneer of Italian farms in the "wine counties."

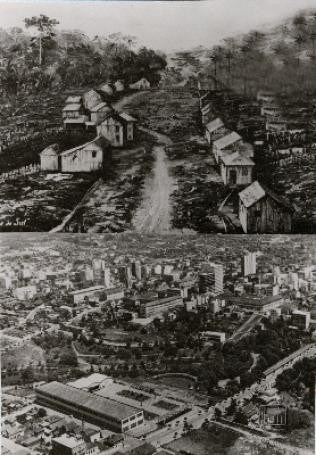

The situation in Latin America was different. In Brazil farmers from the Veneto, Friuli, Trentino and Lombardy founded colonies to which they gave the names of their countries of origin.

In Argentina for example Villa Regina where Italian settlers transformed the desert into orchards, vineyards, plantations of fodder, corn and vegetables.

A singular path of several Italians has been that of town founders. Sometimes small entrepreneurs, working in the railroad construction industry, had the intelligence to precede rather than follow the tracks by purchasing land suitable for future stations and the towns that would spring up around them. That is why some of them are remembered as "town founders."

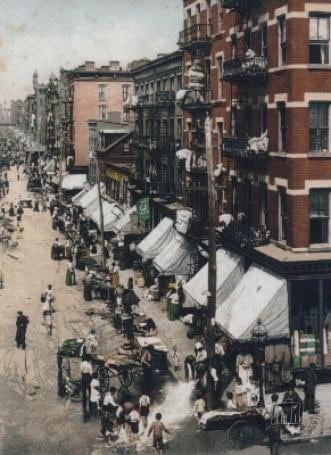

The "little Italies"

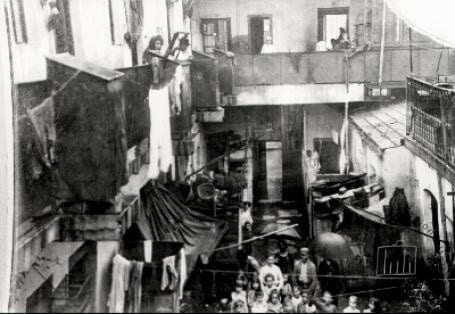

The streets of Little Italy, as the Italian neighborhood was called in the United States, were narrow, crowded, dirty, overgrown by tenements, large dilapidated tenements with shared utilities and the entrance to almost uninhabitable, dark alleys.

The newly arrived immigrant found refuge in "Little Italy," integrating into the group that reproduced familiar values and behavior. In Buenos Aires, the emigrants found lodging in the harbor area, in buildings converted into dwellings, the conventillos: two-story buildings with an inner courtyard where shared services were located.

Conventillos in Buenos Aires and tenements in New York, became centers of reproduction of Italian culture and the origin of Italian neighborhoods in which the streets had the function of the town square, where a cultural heritage, suspended between ancient roots and new "frontiers," could be found.

Sweet Home

The conquest of home became one of the most reassuring "signs" of the path taken and the "progress" made: home is the place where everyone can simply be himself. Home is nest and fortress; refuge for those with "inside Italy, outside America," still largely to be conquered. And the photos are almost biographies written by the emigrants themselves.

Two different accounts: Augustin Storace merchant and bombero (firefighter) in Lima. Provided with a good education, he uses the lens to fix scenes of family life. Benny Moscardini, transplanted to Boston, makes a less private use of photography: he portrays young people and girls in the neighborhood, the streets decked out in honor of General Diaz, and, on a trip to Italy, a dock in New York Harbor.

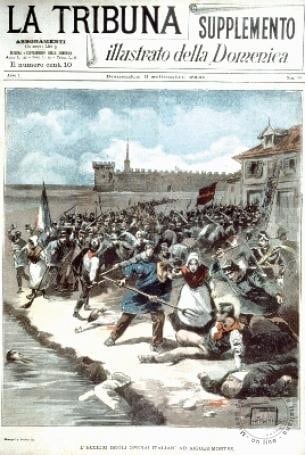

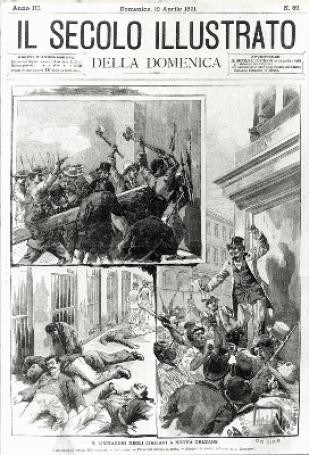

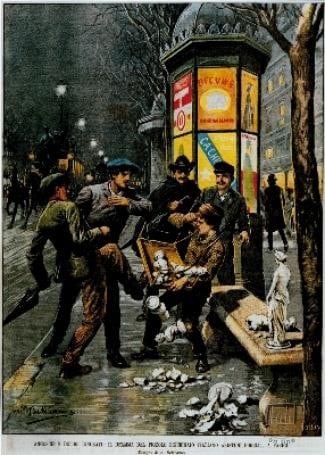

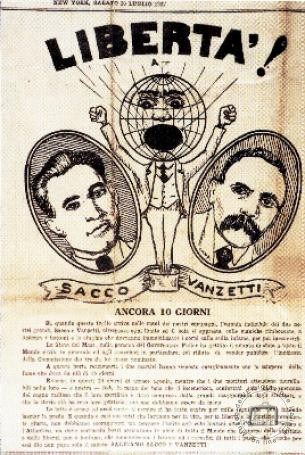

Stories of intolerance

The history of Italian emigration is dotted with tragic episodes of xenophobia, occurring especially in the last decade of the 19th century. In the United States: in 1891, 11 lynchings in New Orleans; in 1893, one in Denver; in 1895, 6 murders in Walsenburg; in 1896, 5 lynchings in Tallulah. In Europe: in 1893, numerous victims in incidents in Aigues Mortes, France; in 1896, 3 murders in Zurich. Many other assaults marked the whole of the great emigration.

Common elements were: racial and cultural prejudices; fears of economic repercussions from the 'influx of immigrants; and the influence of the general political situation. The racially motivated aversion to Italians, considered little more than Negroes results from countless disparaging cartoons published in newspapers in many countries.

Toward a complex identity

To the first emigrants the term "uprooted" fits well: generally they, while coping with the diversity around them, defended themselves from it by learning the language only the bare minimum and maintaining original customs and habits of life. The second generation, often born in the new country, lived uncertain in the choice between a past that could offer some points of reference and a future that was attractive but still had imprecise connotations.

The third and fourth generations turn out to be embedded in the society in which they operate and emerge in politics, arts, finance, cinema, commerce. As the generations integrate, they feel the need to rediscover their roots and seek to recover them in search of identity, a drive that brings together ethnic aspects (religion, festivals, gastronomy) and new lifestyles (work, family, friendships).

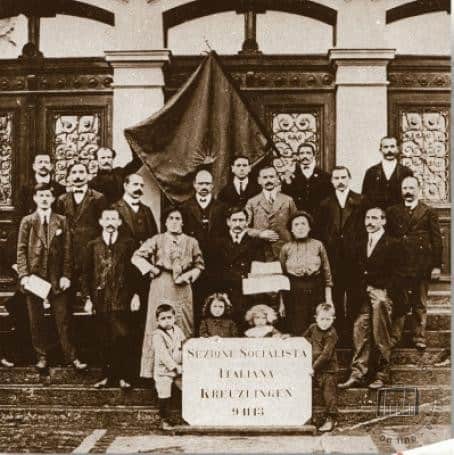

Making group

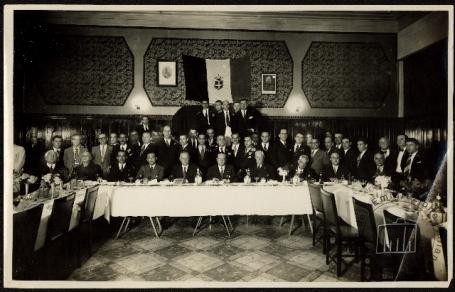

During the "great emigration," associations sprung up for mutual aid among members by helping them overcome difficulties associated with settling into the new reality. Small monthly dues were paid to help those who lost their jobs and to care for the sick. Sometimes the society was combined with a commissary of basic necessities at subsidized prices.

Later, the societies broadened their 'activities: they carried out work placement; provided health education with doctors and clinics; established schools and libraries to teach Italian and improve the technical education of members; and organized social lunches, dances, parties for political and religious occasions, cultural and sports events. At the societies it was possible to follow Italian affairs by reading Italian newspapers.

The school between two worlds

All governments in immigration countries carried out integration work toward foreigners. The man who emigrated alone thought of earning for the livelihood of his own at home and to hasten the time of return and, therefore, refused all contact with the unfamiliar language, with different customs, even those related to leisure. The most effective integration policy put in place by host countries was achieved through schooling and welfare interventions to quickly acquire local customs and habits.

Italian governments realized the importance of maintaining ties with emigrants: a law on Italian schools abroad was passed in 1889; in that year the "Dante Alighieri Society" was born to spread Italian language and culture around the world.

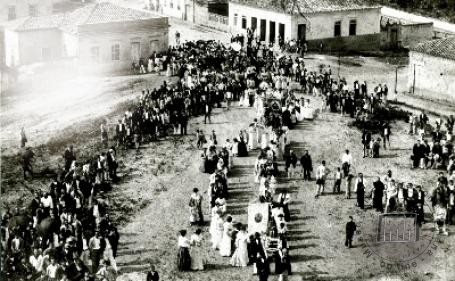

Saints and processions

Religious festivals involved the family and the entire community, and in addition to Christmas and Easter, those of the celebration of patron saints. By participating in them, the emigrants were connected to the life of the community of origin; they felt the saints as their protectors in the event of exile and from whom they could receive comfort and help. The importance of religion in the various Italian communities is demonstrated by the development of places of worship: from the small wooden chapel to the simple stone church and finally to the monumental ones, with tall bell towers, in Italian-inspired architectural styles.